>PepperSupreme (Adding category Candidates_for_deletion (automatic)) |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

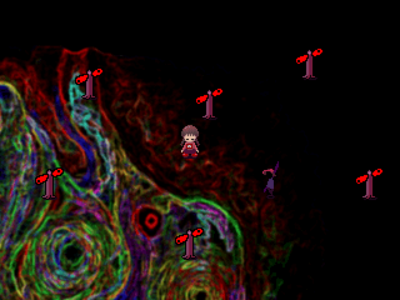

[[File: | [[File:YN Windmill World.png|thumb|400px|link=http://yumenikki.wikia.com/wiki/Windmill_World|The Windmill World. To the right of Madotsuki is the Fisherman.]] | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

↓ | ↓ | ||

[[Madotsuki]]([http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/attached <u>attached</u>] 《[http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/to <u>to</u>]》,[http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/window <u>window</u>]?) → The [http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm#1 <u>Monad</u>]s have (no) [http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm#7 <u>window</u>]s([http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm THE MONADOLOGY]?) | [[Yume Nikki:Madotsuki|Madotsuki]]([http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/attached <u>attached</u>] 《[http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/to <u>to</u>]》,[http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/window <u>window</u>]?) → The [http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm#1 <u>Monad</u>]s have (no) [http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm#7 <u>window</u>]s([http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/classics/leibniz/monad.htm THE MONADOLOGY]?) | ||

'''厳密に相互に独立している(モナドには窓がない)。''' | '''厳密に相互に独立している(モナドには窓がない)。''' | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

: http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%89%AF%E6%BA%90 | : http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%89%AF%E6%BA%90 | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Yume Nikki theoretical discussions by Mt.kiki]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:49, 1 May 2024

Windmill World(THE MONADOLOGY)

1. Matter and Thought

Most of Leibniz's arguments against materialism are directly aimed at the thesis that perception and consciousness can be given mechanical (i.e. physical) explanations. His position is that perception and consciousness cannot possibly be explained mechanically, and, hence, could not be physical processes. His most famous argument against the possibility of materialism is found in section 17 of theMonadology (1714):

- The thought experiment of the windmill by Leibniz

One is obliged to admit that perception and what depends upon it is inexplicable on mechanical principles, that is, by figures and motions. In imagining that there is a machine whose construction would enable it to think, to sense, and to have perception, one could conceive it enlarged while retaining the same proportions, so that one could enter into it, just like into a windmill. Supposing this, one should, when visiting within it, find only parts pushing one another, and never anything by which to explain a perception. Thus it is in the simple substance, and not in the composite or in the machine, that one must look for perception.

↓

Madotsuki(attached 《to》,window?) → The Monads have (no) windows(THE MONADOLOGY?)

厳密に相互に独立している(モナドには窓がない)。

The Monads have no windows, through which anything could come in or go out.

↓

http://yumenikki.wikia.com/wiki/Madotsuki(name)#Mado.28THE_MONADOLOGY.29

Windmill World(哲学的ゾンビ)

ゾンビ論法と類似したタイプの議論、つまり「意識体験」と「物質の形や動き」との間に合理的なつながりが見出せない、というタイプの議論は、歴史上様々な形で論じられている。歴史を下るにつれて議論は洗練されていくが、以下主な例をいくつか列挙する。

ライプニッツによる風車小屋の思考実験

[1][2]思考できる機械(現代的に言えば人工知能)があるとして、その機械を風車ほどまで大きくしたとする。このとき、そのなかに入って周りを見渡したら、いったい何が見えるだろうか。ライプニッツはそこを考えた。17世紀のドイツの哲学者ライプニッツが著書『モナドロジー』の中で、風車小屋(windmill)を引き合いに出して行った次のような論証がある[2]。 ものを考えたり、感じたり、知覚したりできる仕掛けの機械があるとする。その機械全体をおなじ割合で拡大し、風車小屋のなかにでもはいるように、そのなかにはいってみたとする。だがその場合、機械の内部を探って、目に映るものといえば、部分部分がたがいに動かしあっている姿だけで、表象について説明するにたりるものは、けっして発見できはしない。

— ライプニッツ 『モナドロジー』(1714年) 第17節、清水・竹田訳[3]

Windmill World(Philosophical Zombie)

A philosophical zombie or p-zombie in the philosophy of mind and perception is a hypothetical being that is indistinguishable from a normal human being except in that it lacks conscious experience, qualia, or sentience.[1] When a zombie is poked with a sharp object, for example, it does not feel any pain though it behaves exactly as if it does feel pain (it may say "ouch" and recoil from the stimulus, or tell us that it is in intense pain).

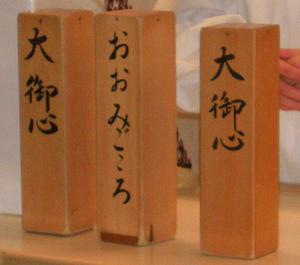

Cube Guru(O-mikuji)

O-mikuji (御御籤, 御神籤, or おみくじ o-mikuji[1]?) are random fortunes written on strips of paper at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan. Literally "sacred lot", these are usually received by making a small offering (generally a five-yen coin as it is considered good luck) and randomly choosing one from a box, hoping for the resulting fortune to be good. (As of 2011[update] coin-slot machines sometimes dispense o-mikuji.)

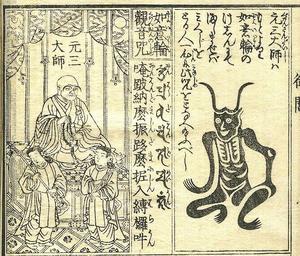

(良源?, 912 – January 31, 985 AD) was a chief abbot of Enryaku-Temple (Enryaku-ji) in the 10th century, and the founder of the tradition of warrior monks (sōhei).

"The founder of the "O-mikuji" looked at by the shrines and temples of the Japan whole country?"